Tashkent metro is one of the landmarks of modern capital. Twenty-nine uniquely designed stations spanning 36 km of track offer a stunning example of Soviet architecture at its best. Largely modelled on the Moscow Metro, Tashkent’s underground system is impeccably clean, safe and runs like clockwork. There are three main lines: the Chilanzar Line, opened in 1977; the Uzbekistan Line (1984); and the Yunusabad Line, (2001), for which an additional eight stations are currently being built or planned. Fourth line, the Sirghali Line, is currently under construction.

Upon entering a Tashkent Metro station, the warm, stale smell found in almost any underground system in the West quickly dissipates once you have purchased your light-blue plastic token and passed the guard barriers. Wide platforms and high ceilings give the impression, in many of the stations, of being in a light, airy, immaculately clean hall. The ubiquitous policemen patrol every platform, which reassures one’s safety concerns.

Relative to the city’s size, the Tashkent Metro has the reach and accessibility of the London Underground, the efficiency of the New York Subway, the simplicity of Rome’s Metropolitana and the roomy carriages of the Métro de Paris.

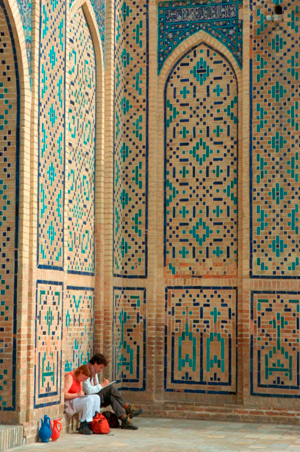

Each station’s architecture and décor are unique, centring on a particular theme – usually some proud aspect of Uzbekistan’s people, history or culture. Ming O’rik (‘Thousand Apricots’) station, for example, pays tribute to that popular fruit and its prevalence in Tashkent. Bodomzor station displays ceramic images of chillies and bread, two important staples of Uzbek daily life. The first station to be built, Mustakillik Maydoni (‘Independence Square’), sits across the road from the Senate building. The marble used in its construction comes from the Kizil Kum desert in western Uzbekistan. Numerous chandeliers brighten the platform and the star patterns in the marble floor represent the contribution made to Uzbek history by Ulug Bek, a fifteenth-century astronomer prince and the grandson of Timur.

One stop from Mustakillik Maydoni on the Chilanzar Line is Pakhtakor station, the second to be completed, which displays beautiful mosaics of cotton – the main cash crop and export of Uzbekistan. Dominating the walls are bronze sconce lamps that resemble early nineteenth-century candelabra. Next to Pakhtakor station, on the Uzbekistan Line, is Alisher Navoi station, named after the fifteenth-century Herat-born father of Turkic literature. Its walls are decorated with scenes from this famous poet’s work. Thanks to its domed architecture, Alisher Navoi stays cool even during the height of summer.

Two stops from Alisher Navoi to the south is Kosmonavtlar station, dedicated to Soviet space travel. Images of cosmonauts line the walls, including those of the first human in space, Yuri Gagarin, and the first woman in space, Valentina Tereshkova. The station’s large grey pillars lead up to its dark ceiling, and the clever use of both dim and bright lighting gives it a celestial feel.

One could spend days exploring the Tashkent Metro in detail. The uniqueness of each station is awe-inspiring, and there is a general sense of anticipation when approaching the next stop. It is said that the Metro was a reward for the sacrifices made by Tashkent’s citizens during the 1966 earthquake; for the city’s inhabitants it is a mark of pride, and for the foreign tourist, the object of envy and marvel.