Bukhara, which is situated on the Great Silk Road, is more than 2,000 years old. It is the most complete example of a medieval city in Central Asia, where whole districts with their ancient layouts have been preserved to the present day. Monuments of particular interest include the famous tomb of Ismail Samani, a masterpiece of 10th-century Muslim architecture, and a large number of 17th-century madrasas. The historic part of the city, which is in effect an open-air museum, combines the city’s long history in a single ensemble.

The Samanids Mausoleum. The Samanids Mausoleum is the oldest structure in Bukhara, which remained intact to the present day. It was built in the late 9th-early 10th centuries for Ahmed ibn Asad by order of his son Amir Ismail Samani, the founder of the first centralized state in Central Asia. Later he himself was interred in the mausoleum. In 943, the body of Ismail’s grandson Nasr was also committed to the ground in this burial vault.

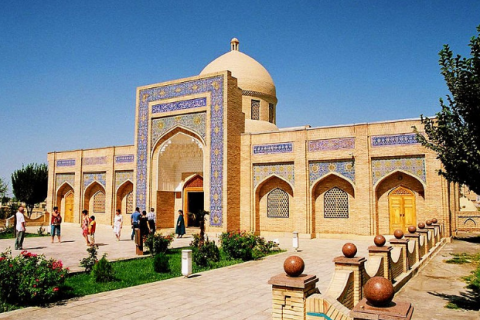

Miri-Arab Madrasah. Among the large number of the madrasahs built in Bukhara in the 16th century, Miri-Arab Madrasah stands out as a true masterpiece. It was built on an elevated platform right across from the Kalyan Mosque. This architectural technique, called kosh (“coupled”), was quite common in the Middle Ages. After Miri-Arab Madrasah had been constructed, Poi Kalyan Square reached its completion. Miri-Arab Madrasah is still one of the world’s most famous and largest Islamic colleges.

Modari-khan Madrasah. To the southwest from Ark, on the ancient Khiyobon street, which once ran to the Shir-Garon city gate, stands the architectural complex Kosh-madrasah (“coupled.”), consisting of two madrasahs with facades located on the same line. This architectural design was frequently used in Asia in the Middle Ages. Kosh-madrasah was completed in the second half of the 16th century, during the rule of emir Abdullakhan.

Ulugbek Madrasah. Amir Temur’s son Mirzo Ulugbek, who ruled Movarounnahr in the first half of the 15th century, built three madrasahs. The first one was constructed in Bukhara in 1417. By that time, Bukhara had been long since known as the capital of Islamic theology. In the Orient and at all times, madrasahs were centers of science and education. It was no wonder that on the instructions of Ulugbek, a well-educated monarch who was often called “the scientist on the throne,” there was carved the following aphorism on the richly decorated entrance door: “Seeking after knowledge is the duty of every Muslim man and woman.” Another inscription was made on the nearby bronze plate for knocking: “Let the door of God’s blessing be opened to the circle of people, over and above the wisdom of books.”

Abdulazizkhan Madrasah. In 1652, opposite Ulugbek Madrasah, Bukhara’s ruler Abdulazizkhan, ordered to build a new madrasah, whose grandeur and luxury of decoration had to surpass all other madrasahs. And indeed, although the general design of the madrasah followed 15th century architectural canons, the great dimensions and rich decoration allowed this structure to be ranked with the most outstanding architectural monuments of Uzbekistan.

Lyabi-Khauz architectural complex is located in the centre of Bukhara and consists of three monumental edifices. The complex possesses a distinctive character: contrary to conventional traditions of making the city square or street junction the centre of an architectural complex, it was constructed around a large khauz (pond).

Nadir Devanbegi, the emir’s uncle, had much influence on state affairs, and in the absence of the ruler, even negotiated on his behalf with foreign envoys. Taking advantage of his authority, he intended to construct a profitable caravanserai on the bank of the pond just opposite the khanaka. However, Imamkulikhan was very hard on his men, both retinue and the relatives. When the caravanserai was finished, Nadir Devanbegi invited the ruler to the opening ceremony.

Sitorai Mokhi-Khosa Palace. Of the numerous country palaces in Bukhara, Sitorai Mokhi-Khosa, the summer residence of the last Bukhara emirs, survived the best. The palace is located at a distance of 2.5 miles north from Bukhara, by the road that runs to Gijduvan.

The Ark Fortress. To the northwest of the center of the city there is, perhaps, the oldest building of Bukhara─the Ark fortress. Its high, gentle walls for more than one and a half thousand years defended its emirs and rulers, and now delight the guests and residents of the city by its monumentality. Today, many buildings inside the citadel are destroyed and only one gate has survived, but the spirit of time is felt in every brick, every stone.

Bolo-Khauz Mosque. To the west of Ark Fortress, long before Bukhara was conquered by the Arabs, there had emerged a busy city center─Registan Square. In the 17th century, the area on the approaches to the square used to be occupied by rows of market shops.

Abdullakhan Tim. In Asia, trade has always been considered a respectable occupation. In Noble Bukhara, there were always busy bazaars and the doors of the shops lining the streets stood invitingly open. Yet, in the 16th century, they also started to build in the town huge roofed shopping passages. Such a passage was called tim. One of them still exists: Abdullakhan Tim, which was named after its constructor, a ruler from the Sheibanids dynasty.

Bahouddin Naqshbandi Complex. In the suburbs of Bukhara, there stands an architectural memorial to the great Sufi, hermit, and saint Sheikh Bahouddin Naqshbandi, who made an invaluable contribution to the formation and development of Central Asian progressive thought.

Nakhsbandi was born to the family of a weaver in a small village near Bukhara in 1318. Early in life, he excelled at weaving patterned silk fabrics. So it was not without reason that he eventually became known as the patron saint of handicraftsmen. Among his teachers and spiritual tutors were such outstanding personalities as Hajji Samosi and Shamsiddin Mir Kulol, Amir Temur’s confessor. Having developed his own doctrine, Bahouddin Naqshbandi founded the Sufi order Naqshbandiya.